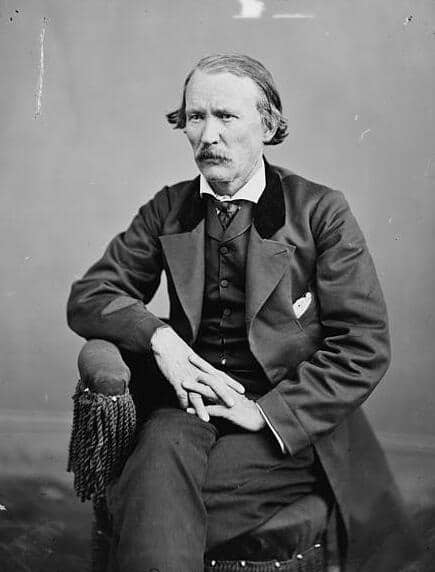

Kit Carson was a legendary American frontiersman, scout, and explorer who played a significant role in the expansion of the United States in the 19th century. Born in 1809, Carson gained fame for his extraordinary skills as a wilderness guide and his pivotal role in various explorations and military campaigns. He worked as a fur trapper, a guide for John C. Fremont’s expeditions, and served as an Indian agent for the Ute and Navajo tribes.

Carson’s reputation grew as he became involved in conflicts with Native American tribes, particularly during the Mexican-American War and the conquest of New Mexico. He was known for his daring and cunning strategies, which earned him respect among both Native Americans and fellow frontiersmen.

In his later years, Carson settled in New Mexico and served as a rancher and military officer. He led a largely peaceful life, advocating for Native American rights and supporting conservation efforts.

While celebrated for his frontier skills and achievements, Carson’s legacy is not without controversy. His involvement in conflicts with Native Americans, leading to their displacement and suffering, remains a contentious aspect of his history. Nevertheless, Kit Carson remains an iconic figure of the American West, symbolizing the rugged spirit of exploration and adventure that characterized the era of westward expansion.